Equal Temperament

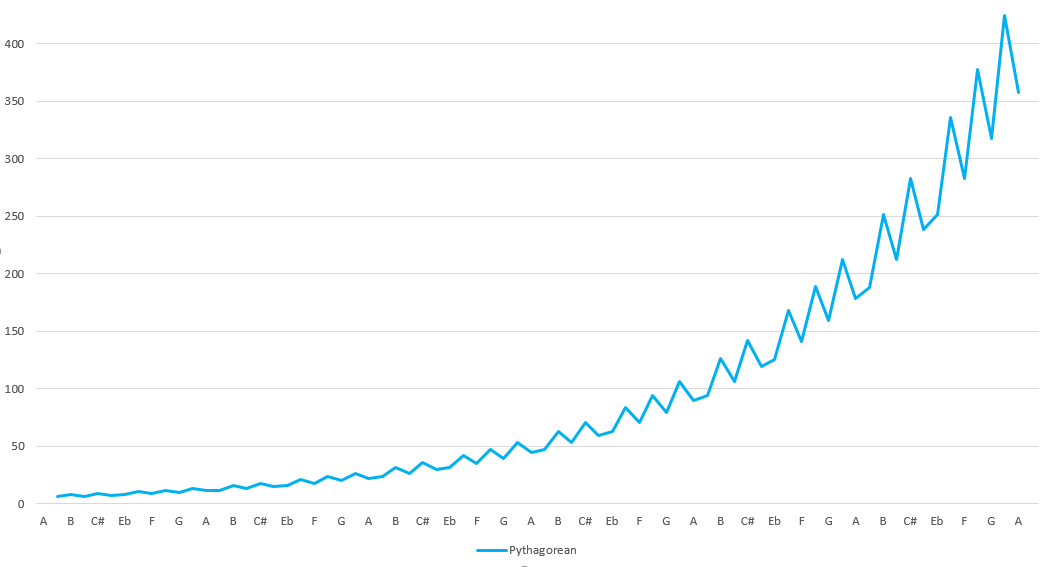

The Baroque PeriodFor most of musical history, instruments had been tuned according to the discoveries of Pythagoras, generally using the pure 2:3 ratio of a perfect fifth. However, this system resulted in the Pythagorean Comma, a discrepancy that arises when stacking notes in seven octaves versus twelve fifths to arrive at the same note, since (3/2)12 ≠ (2/1)7.

| Octaves (1:2 ratio) | |||||||

| A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A |

| 110 | 220 | 440 | 880 | 1760 | 3520 | 7040 | 14080 |

| Fifths (2:3 ratio) | ||||||||||||

| A | E | B | F♯ | C♯ | G♯ | D♯ | B♭ | F | C | G | D | A |

| 110 | 165 | 247.5 | 371.25 | 556.88 | 835.31 | 1252.97 | 1879.45 | 2819.18 | 4228.77 | 6342.15 | 9514.73 | 14272.1 |

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, musicians experimented with meantone temperament, where the perfect fifth was slightly flattened ("tempered") to preserve the pure 5:4 ratio of a major third. However, this system only allowed a small range of key signatures to sound in tune, and the ratios between semitones varied widely. This limited composers' ability to modulate between different keys.

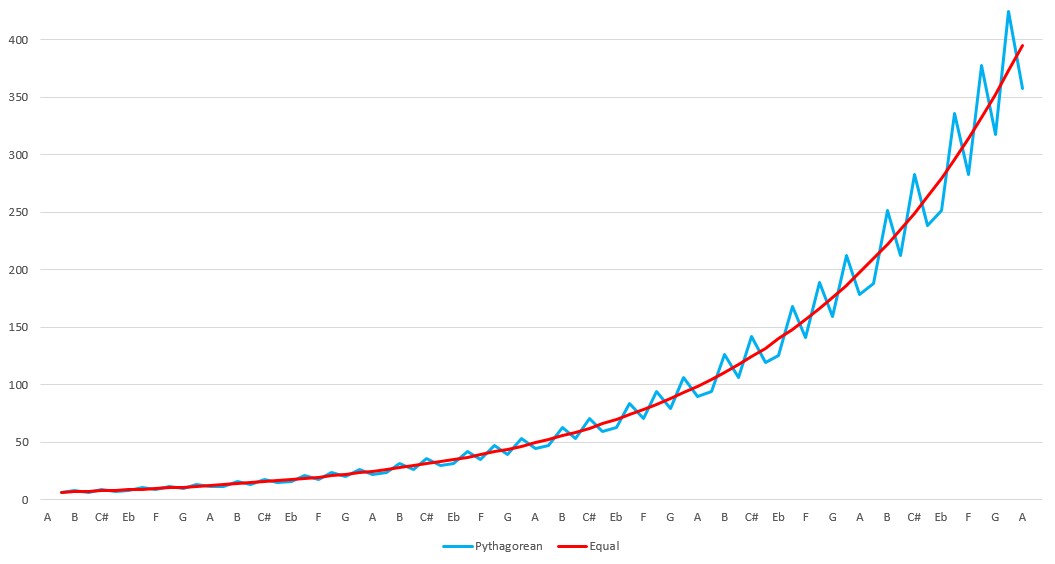

A solution was invented in the early eighteenth century with the advent of equal temperament. In this system, the octaves are tuned at a 1:2 ratio and the frequencies of the other eleven semitones are evenly distributed across the remaining space along the trend line of the Pythagorean intervals.

Technically, this makes every note and every interval (except the octaves) slightly out of tune. In practice, however, the difference is slight and it takes a skilled musician to notice the difference; singers and most instruments can easily adjust their intonation to pure interval ratios as necessary.

Equal temperament allowed a keyboard instrument to play equally well (or equally poorly, depending on your point of view) in all twelve keys. An excited Johann Sebastian Bach composed a set of twenty-four piano études titled The Well Tempered Clavier, one for each major and minor key. This opened up a whole new range of possible harmonic vocabulary, as instruments were no longer restricted to closely related keys.