Richard Wagner

The Romantic Period

Pierre Petit, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Richard Wagner was born in 1813 in Napoléon-occupied Leipzig, the same city in Saxony where Johann Sebastian Bach had spent his career. His father died when he was young, and his mother remarried and moved to Dresden.

Early on, Wagner was more interested in theater than music. He did learn to play the piano, but not very well. His stepfather and older brothers were all involved in the theater, and he loved European mythology and Shakespeare. At the age of 13, he wrote a play based on Shakespeare's tragedies called "Leubald," in which he killed 42 different characters and had to bring them back as ghosts or else the play would have been too short.

In 1827, the year after Beethoven died, Wagner's family moved back to Leipzig, and he heard the Seventh and Ninth Symphonies for the first time. It was upon hearing these that he decided to pursue music, writing, "I only remember that one evening I heard a symphony of Beethoven's for the first time. It set me in a fever, and in my recovery, I had become a musician." At Leipzig University, Wagner studied composition, but was a bad student and resisted his instructors until one told him, "You have to learn the rules if you want to break them."

He wrote a symphony but turned quickly to operas. In 1834 in Magdeburg, where he met Minna, whom he married in 1836. His first opera, "Liebesverbot," was based on Shakespeare's "Measure for Measure" but was not a success and left the young couple bankrupt. Wagner took a job in Riga, in the Russian Empire, but got into so much debt that he fled to London to escape his creditors. The couple eventually settled in Paris where Wagner wrote "Rienzi" and "Die Fliegende Holländer." Returning to Dresden in 1842, Wagner became conductor of the Dresden Opera House and got his operas produced. Although "Rienzi" was successful, "Die Fliegende Holländer" was not (but Franz Liszt liked it.) Wagner became active in radical left-wing politics, moving among socialist German nationalists and Russian anarchists. After the Revolutions of 1848, he had to flee to Zürich, Switzerland, to escape the authorities.

While in exile, Wagner wrote two treatises on music. In the first, he described his vision of opera as a Gesamtkunstwerk, a "total work of art," incorporating music, costuming, special effects, scenery, and the integration of all elements toward a complete production. The second treatise was called "On the Jews in Music," was a raging anti-semitic rant.

Paul Hermans, CC BY-SA 4.0

Wagner wrote "Lohengrin," while in Zürich, which Franz Liszt premiered in 1850. (Wagner couldn't attend the premiere because, you know, he was hiding in Switzerland.) In 1852, he met Otto and Mathilde Wesendonck, who gave him a number of loans and a cottage at their estate. For additional money during this period, he traveled to London and gave concerts for Queen Victoria. Wagner then returned to Switzerland and had an affair with Mathilde Wesendonck, while writing the opera "Tristan und Isolde" about an ill-fated love affair. His wife Minna left him and went back to Germany. Wagner went to Venice, then Paris, and then returned to Dresden in 1862, still living off of financial support he was receiving from Otto Wesendonck.

In 1864, King Ludwig II of Bavaria summoned Wagner to his palace and offered to become his patron. The king paid off all his debts, built him a castle, and staged many of his operas. The first opera Wagner wrote for Ludwig was "Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg," which was a great success, followed by "Tristan und Isolde" in 1865. The conductor of "Tristan und Isolde," Hans von Bülow, was married to the daughter of Franz Liszt, Cosima, with whom Wagner had another affair.

King Ludwig, who now had a bit less to do now that Bavaria was just a part of Kaiser Wilhelm's German Empire, financed the construction of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus. This massive opera house was specifically designed to stage Wagner's operas, and hosted the premiere of his magnum opus, "Der Ring des Niebelungens," commonly known as "The Ring Cycle," in 1876. The Ring Cycle is a massive, 16-hour long work of Norse mythology, divided into four operas.

Because the "The Ring Cycle" is so long and composed on such a colossal scale, traditional musical forms like binary, theme and variations, or sonata-allegro are impractical as supporting structures. Instead, the work is story-driven, with each character, setting, and theme coupled with a unique musical fragment called a leitmotif. The musical elements of these motifs can be varied based on whatever situation the story dictates.

Leitmotif is commonly used in modern filmmaking, especially in longer films such as Howard Shore's score to The Lord of the Rings or John Williams' music for Star Wars:

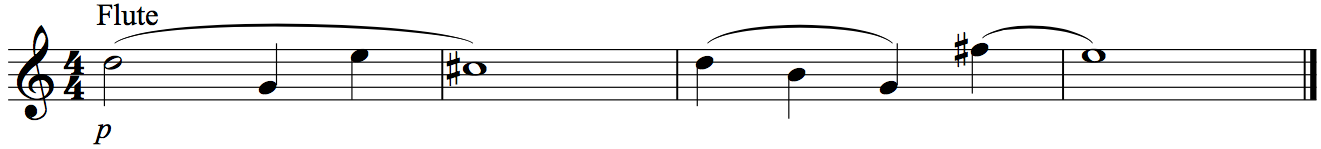

Yoda and the Younglings

As the children practice, Yoda's leitmotif is presented softly in the flute in G major.

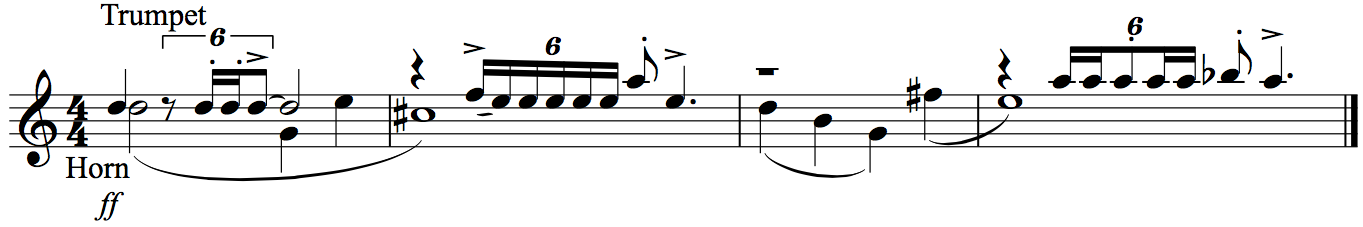

Yoda vs. Count Dooku

While Yoda battles the villainous Count Dooku, the theme is presented forte in the horns, interspersed with fanfare statements in the trumpet.

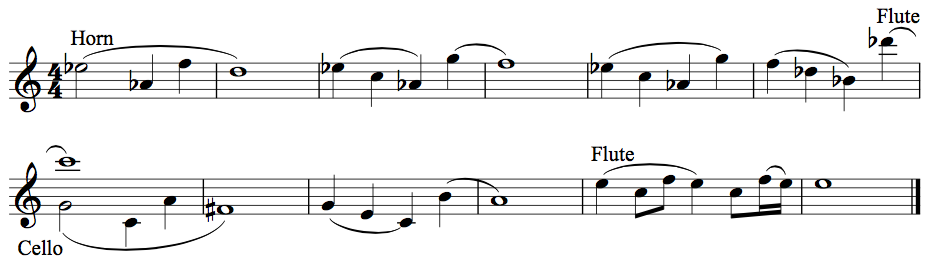

Yoda's Death

As Yoda gives his parting words to Luke Skywalker, the leitmotif is played somberly in the horn in A♭ major. The theme then passes to the cello in C major, before the flute gives a final warning in A-minor, based on the leitmotif in augmentation.

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial

In E.T., which is not a Star Wars movie (or is it?), but is also scored by John Williams, the leitmotif is heard when a child walks by in a Yoda costume on Halloween.

Wagner's final opera was a legend about the Holy Grail, "Parsifal," which premiered in 1882. Wagner died on a trip to Venice the following year.