Classical Greece

Classical Antiquity

In 480 BC, Xerxes, the King of Persia, led an invasion of mainland Greece. Its success should have been a formality. For seventy years, victory - rapid, spectacular victory - had seemed the birthright of the Persian Empire. In the space of a single generation, it had swept across the Near East, shattering ancient kingdoms, storming famous cities, putting together an empire that stretched from India to the shores of the Aegean. As a result of those conquests, Xerxes now ruled as the most powerful man on the planet. Yet somehow, astonishingly, against the largest expeditionary force ever assembled, the Greeks managed to hold out. The Persians were turned back. Greece remained free. Had the Greeks been defeated in the epochal naval battle at Salamis, not only would the West have lost its first struggle for independence and survival, but it is unlikely that there would have ever been such an entity as the West at all.

The Greco-Persian Wars

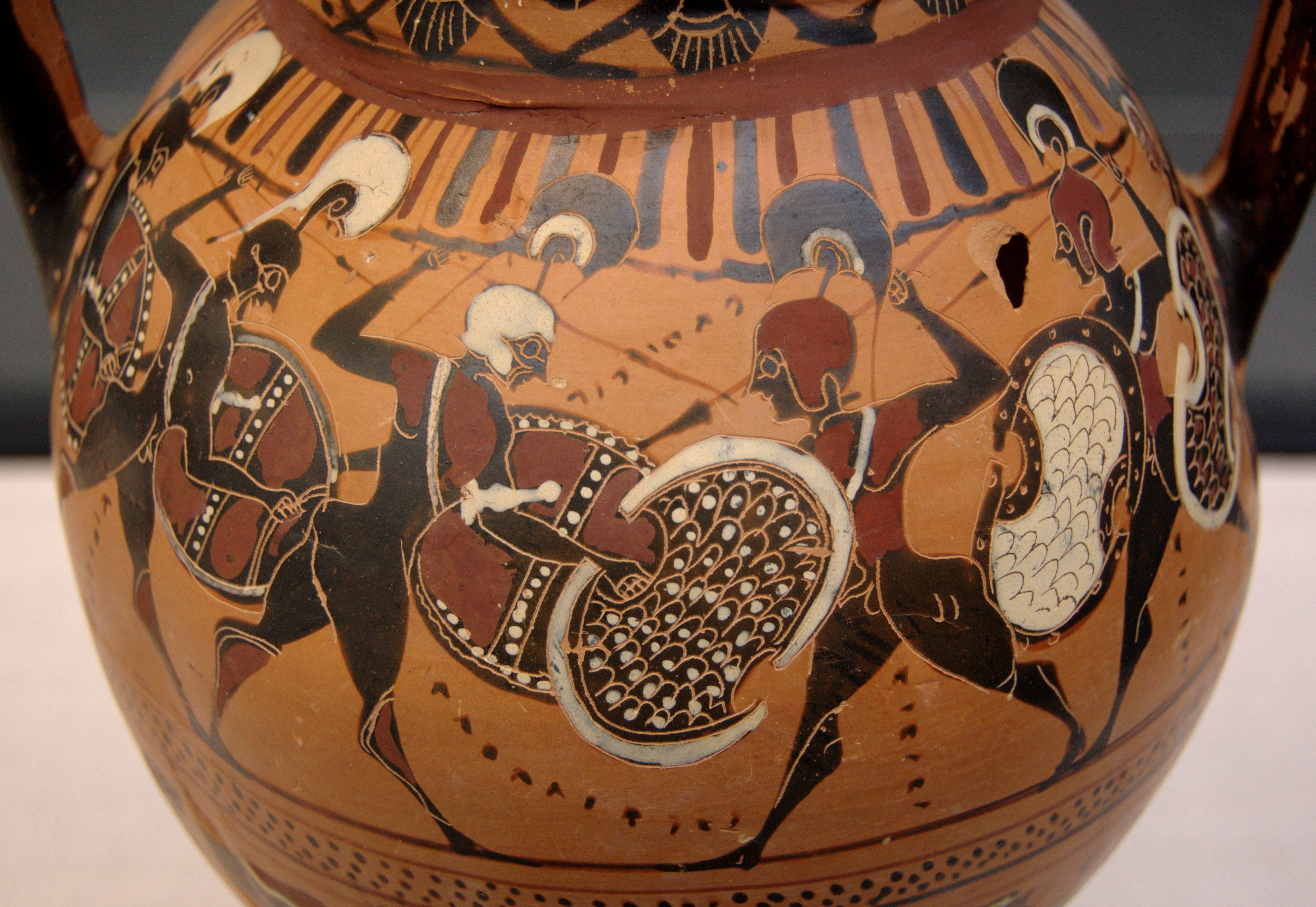

In 500 BC, the Greek city-states in Anatolia rose up against the rule of the Persian Empire in what was known as the Ionian Revolt. The Persians put down the revolt, but since Athens had helped, King Darius used this as an excuse to invade Greece, beginning the Greco-Persian Wars. In 490, Darius landed a substantial force near the Greek city-state Marathon, where they met the Athenian army. Though the Persians outnumbered the Athenians significantly, they were unprepared to fight against a phalanx, a tactic in which the Greeks locked their heavy bronze shields together to form a solid wall, thrusting from behind with long spears. The Persians routed, with a few survivors escaping by sea.

Ten years later, Darius' successor Xerxes tried again. He marched an enormous force into Greece (about a quarter million soldiers) but was held up for three days by a tiny force of Spartans and Thespians commanded by King Leonidas at the narrow pass of Thermopylae. The Spartans and Thespians fought to the death, giving the other city-states enough time to evacuate Athens and prepare for a larger battle. Under their leader Themistocles, the Athenian navy defeated the Persians at Battle of Salamis. The Persian land forces were driven from Greece for good at the Battle of Platea in 479 BC.

The Peloponnesian War

After the Persian Wars, Athens founded the Delian League, an alliance of over 300 Greek city-states. The League's purpose was to keep fighting Persia, but Athens began to use it as its own personal Empire. Eventually the enormous growth in Athenian power led to tension with other Greek city-states. Sparta, in particular, contested Athens' rising influence over city-states in the Peloponnesus, the landmass in southern Greece on which Sparta is situated.

In 431 BC, Athens used a brief war between Megara and Corinth to seize control of the Isthmus of Corinth, the narrow strip of land connecting mainland Greece (where Athens was located) to the Peloponnesus. This led to outright conflict between Athens and Sparta known as the Peloponnesian War. At first, Athens' navy gave it an advantage, but the Sparatan military establishment was still unrivaled.

The Spartan general Lysander defeated the Athenian navy at Aegospotami in 405 BC, and Athens surrendered. Greece was then dominated by Sparta for several decades, but the militaristic Spartans proved poor administrators. The Peloponnesian War weakened all the Greek city-states, leaving them vulnerable to ambitious neighbors.

Alexander the Great

In the wake of the Peloponnesian War, King Philip II of Macedonia, moved to conquer all the Greek city-states, uniting all of Greece with the exception of Sparta. However, when Philip II was killed by a Persian assassin, his son Alexander the Great rose to the throne and launched one of the most legendary military campaigns in history, completely destroying the Persian Empire, conquering Anatolia, Syria, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and even invading India. Alexander died in 323 BC at the age of 32, having made the Macedonian Empire one of the largest polities in history. He is usually regarded as the greatest general of all time and one of the most influential people in history. He is responsible for spreading Greek culture throughout much of the world, launching what is known as the Hellenistic Period (from "Ελλάς," the Greek word for Greece.)

Upon Alexander's death, his empire was divided among his various generals. Eventually, three main partitions developed: the Ptolemaic Kingdom (named after Ptolemy Soter), encompassing Egypt and Palestine; the Seleucid Kingdom (named after Seleucus Nicator), encompassing Mesopotamia and Persia; and the Antigonid Kingdom (named after Antigonus Monophthalmus), encompassing Macedonia and parts of Greece.