Medieval Notation

The Medieval Period

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

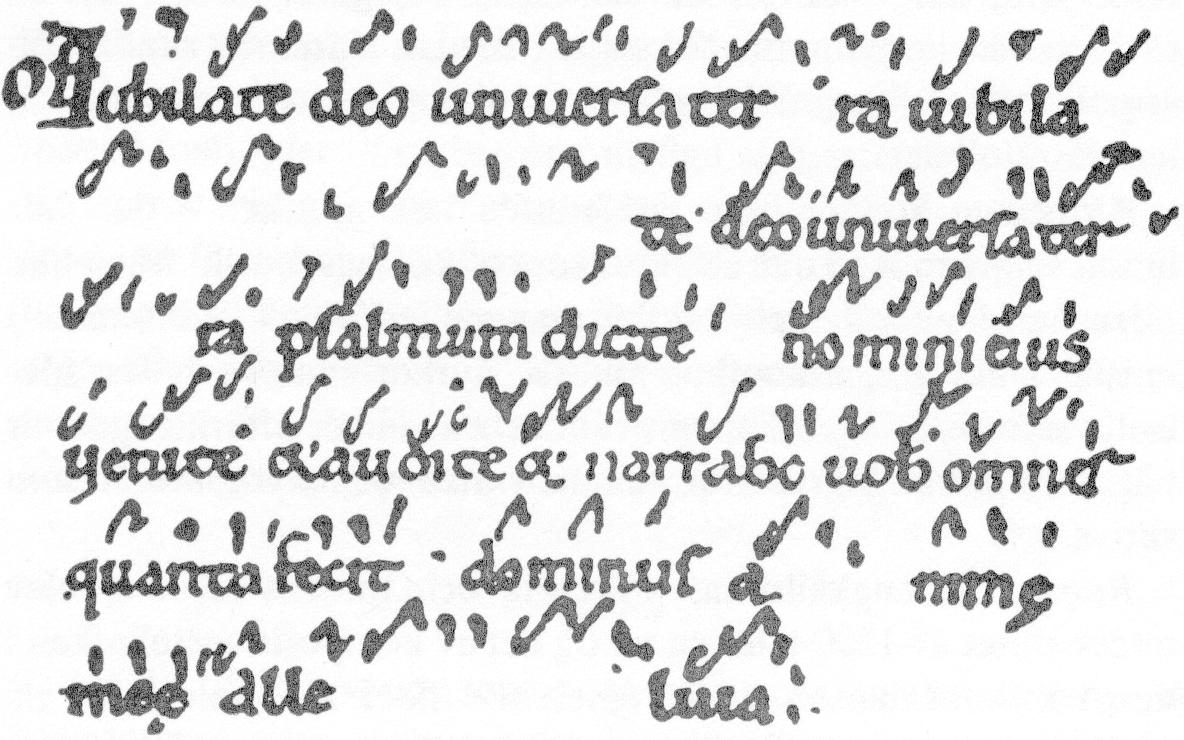

With a large body of liturgical music to memorize, monks in the medieval period began seeking ways to improve musical notation.

Early medieval notation used a series of symbols, called neumes, which were placed above the text of a song to indicate the general contour of the melody. This was somewhat useful as a mnemonic device for melodies already known, but not much use as an aid to learning new music.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A later development involved the addition of a single line between the text and the neumes. This helped to clarify how high a pitch was indicated by each neume, by providing a reference point. Whereas the earlier system provided only a general idea of the melody's rise and fall, pitches could now be determined by their distance above or below the line.

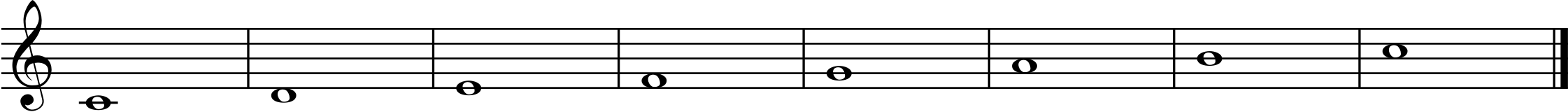

Around the turn of the second millennium, an Italian monk named Guido d'Arezzo further improved this system by adding an additional three lines, such that each line or space represented a distinct pitch. This is called the staff and, save one additional line, is the same system we use today. The invention of the staff allowed musicians to visualize music in a way previously not possible, and marks the moment that Western European music truly begins to diverge from the musical traditions of the rest of the world. Guido d'Arezzo's system was presented to Pope John XIX (r. 1024 - 1032), who after learning it was delighted to sing melodies he had never heard before. The system soon became standard throughout Europe.

Each tone of the scale, or scale degree, has a special name given to it by medieval music theorists in some way indicating its role.

| 1 | Tonic | The Latin word "tonus" means "note" and refers to the first note of the scale, by which all the others are measured. |

| 2 | Supertonic | The second scale degree is called the "supertonic," meaning "above the tonic." |

| 3 | Mediant | Scale degree 3 is called the "mediant," being half way between the tonic and the dominant. |

| 4 | Subdominant | The "subdominant" is not so named by virtue of being a step below the dominant, but rather because it is a dominant (fifth) below the tonic. |

| 5 | Dominant | A fifth above the tonic at a 2:3 frequency ratio. |

| 6 | Submediant | Scale degree 6 is called the "submediant" because it is half way between the tonic and the subdominant. |

| 7 | Subtonic | The seventh scale degree is called the "subtonic," meaning "below the tonic." If the subtonic is a semitone below the tonic, it is called a "leading tone." |

Pierdeux, CC BY-SA 4.0

The hymn Ut Queant Laxis, with lyrics invoking the prayers and aid of Saint John the Baptist, was written using Guido d'Arezzo's notation system. Each phrase of the hymn begins one step above the previous phrase. Note that first syllable of each line (ut, re-, mi-, fa-, sol-, la-) became the basis of the solfege system. Eventually, "si" and later "ti" was added to indicate the seventh tone, and "do-" (the beginning of the word Dominus, "The Lord") replaced ut to swap the consonant and vowel order. With these modifications, the solfege system is still widely in use today, essentially the same as when Guido d'Arezzo developed it.